Life is a series of transitions, from the exciting to the challenging. Getting your first job, moving to a new city, buying a home, getting married, having children, changing careers, or even navigating a major health event – each of these milestones comes with significant financial implications that, if not properly managed, can quickly turn a moment of joy into a source of stress. This is where financial literacy for life transitions becomes your ultimate GPS, guiding you through unfamiliar territory with confidence.

Most financial advice focuses on general principles: save more, spend less, invest wisely. While invaluable, these broad strokes often miss the specific, complex financial nuances that arise during life’s major shifts. Understanding these unique financial landscapes before you enter them can be the difference between thriving and just barely surviving.

The Hidden Costs of Milestones

Let’s explore some common life transitions and why a tailored financial understanding is crucial:

1. First Job / Moving Out: Beyond the Rent Check

The excitement of independence often blinds young adults to the full cost of living on their own. It’s not just rent; it’s utilities, groceries, transportation, health insurance (if not provided by an employer), furnishing a place, and the often-overlooked “setup costs” like security deposits. Financial literacy here means understanding budgeting, setting up emergency savings, managing student loan payments, and beginning to build credit responsibly.

2. Marriage / Merging Finances: Two Become One (Bank Account)

Combining lives means combining financial philosophies, debts, and assets. This transition requires open communication, shared goal setting, and often, difficult conversations about past financial habits. Key literacy areas include creating a joint budget, deciding on joint vs. separate accounts, understanding each other’s credit scores, managing existing debts, and updating beneficiaries on financial accounts. It’s about building a unified financial vision for your shared future.

3. Buying a Home: More Than Just the Mortgage Payment

The down payment and monthly mortgage are just the tip of the iceberg. Homeownership comes with property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, maintenance costs (often 1-3% of the home’s value annually), potential HOA fees, and closing costs that can add thousands to the initial expense. Financial literacy for homebuyers includes understanding different mortgage types, assessing affordability beyond the monthly payment, saving for a substantial emergency fund, and knowing how to budget for ongoing home expenses.

4. Having Children: The Priceless Addition with a Price Tag

Raising a child is one of life’s greatest joys, but it’s also a significant financial undertaking. From diapers and formula to childcare, education savings, increased healthcare costs, and extracurricular activities, the expenses add up rapidly. Financial preparation involves adjusting budgets for new recurring costs, understanding tax credits for dependents, exploring college savings plans (like 529s), and critically, updating life insurance and wills to protect your growing family.

5. Career Change / Entrepreneurship: The Leap of Faith

Whether you’re moving to a new industry or starting your own business, a career transition often involves a period of reduced or unstable income. Financial literacy here means building a robust emergency fund (ideally 6-12 months of living expenses), understanding unemployment benefits (if applicable), budgeting for potential training or startup costs, and for entrepreneurs, learning about business finance, taxes, and cash flow management.

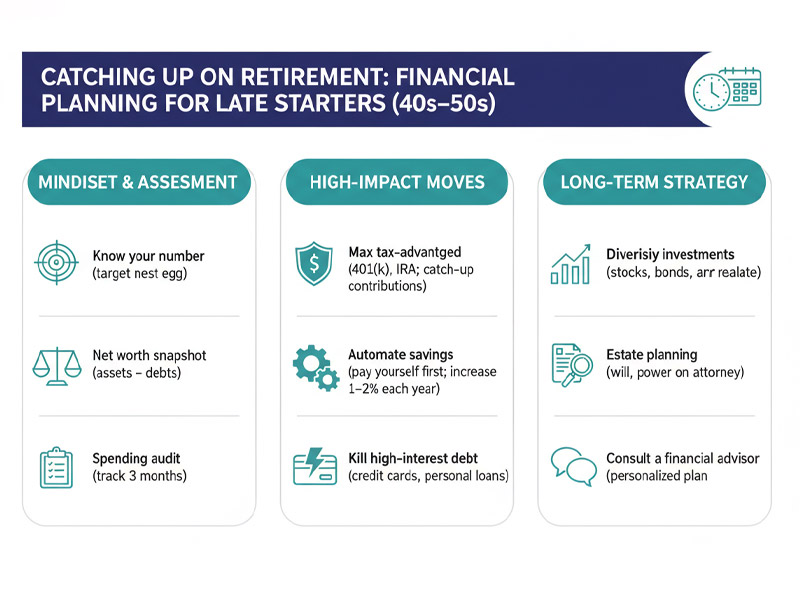

6. Retirement Planning: The Grand Finale (and New Beginning)

While retirement planning starts early, the years immediately preceding and during retirement are critical. This transition involves shifting from accumulating assets to drawing them down. Financial literacy means understanding Social Security benefits, managing investment withdrawals strategically to minimize taxes, navigating healthcare costs in retirement (including Medicare and long-term care), and ensuring your estate plan is in order. It’s about ensuring your nest egg lasts as long as you do.

The Lifelong Learner Advantage

The common thread through all these transitions is the need for proactive learning and planning. Financial literacy isn’t a one-time course; it’s a continuous process of acquiring knowledge and adapting strategies as your life unfolds.

By understanding the financial landscape of an upcoming life transition, you gain:

- Reduced Stress: Knowing what to expect and having a plan alleviates anxiety.

- Better Decision-Making: You make informed choices, avoiding costly mistakes.

- Increased Resilience: You build buffers to withstand unexpected challenges.

- Empowerment: You take control of your financial destiny, rather than feeling controlled by circumstances.

Don’t wait for a life event to force your hand. Anticipate, educate yourself, and plan. Treat financial literacy as your essential companion for every chapter of your life’s journey. It’s the tool that transforms uncertainty into opportunity, allowing you to embrace each transition with an open heart and a well-prepared wallet.